On this date of January 1, 1863, President Lincoln would give his signature to one of the greatest documents in American history. One would think it to be a great day for the 16th president, and indeed, he was confident and pleased with the action. But most of the day was not honestly that awesome; rather it was tiring, stressful, and burdensome.

News of War efforts brought little optimism. On this day, the federal garrison at Galveston would surrender to a Confederate attack. The William T. Sherman attack on the bluffs at Chickasaw Bayou had too many similarities to the frontal attacks of Burnside at Fredericksburg – still fresh in memory as Washington hospitals brimmed with the wounded from such. The moderate success of Rosecrans at Stones River was yet to be learned.

Lincoln’s day began with a meeting with Burnside, the General having been ordered by the President to not make a movement across the Rappahannock without advising Washington. So Burnside obliged by coming to the White House to confer with Lincoln – who was aware of the possibilities of a movement by the unannounced visit of two Army of the Potomac subordinates. Generals John Newton and John Cochrane had come on the 30th to apprise Lincoln of the troublesome plans and to bring to his attention the lack of confidence in Burnside possessed by the Army. The President was able to see this as a thinly veiled attempt of the McClellan crowd to promote the Little Napoleon’s reinstatement. But nonetheless, it was a problem.

As the two men met, Burnside acknowledged his awareness of the lack of confidence of subordinates, and in typical fashion expressed his openness to seeing another put in his place. But more boldly, Burnside suggested that Lincoln had greater problems on his own hands and in his own house in the persons of Stanton and Halleck – men whom he said had not served the army, the president, or the country well. There was certainly truth to the problems Lincoln had with his Cabinet – having recently weathered several attempts at resignations, and needing also to deftly work through ongoing strife.

On this occasion, Lincoln asked Halleck to go to the field, observe the situation, and render an opinion and directive on the matter. Halleck did not believe this was an appropriate role for him to overrule generals in the field, and offered his resignation as general-in-chief. This Lincoln could not endure at the time and therefore rescinded the order, though he would later say of Halleck that he was little more than a first-rate clerk.

Next on the agenda from 11:00 to 2:00 was a large reception and three hours of hand-shaking. Next to him was his wife still dressed in black in mourning for the death of Willie. Finally, with a sore arm and numb hand fatigued such that holding a writing implement was questionable, Lincoln took to signing the document. He said, “This signature is one that will be closely examined, and if they find my hand trembled, they will say ‘he had some compunctions.’ But any way, it is to be done.” He also commented, “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper.”

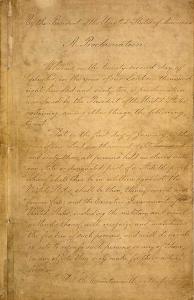

BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A Proclamation

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.